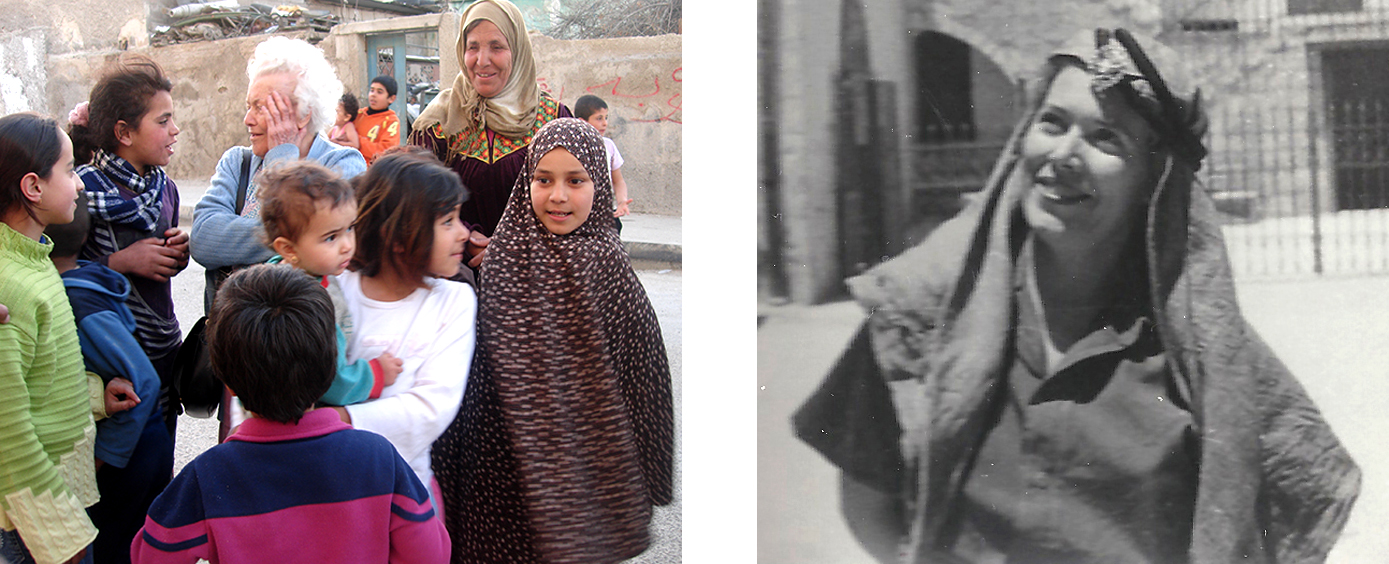

In Memoriam

With the Children of al-Wahdat Camp 2008

1948 Palestine War, with the Arab Legion, Jerusalem

With the Children of al-Wahdat Camp 2008

1948 Palestine War, with the Arab Legion, Jerusalem Free French Resistant (1939-1945), journalist and teacher, ‘‘Hajja’’ and ‘‘Great-Grandmother’’ of the children of the Palestinian Refugee Camps of al-Baqa’a and al-Wahdat, Amman.

Part I: Discovering and Measuring the Land >>

Part I: Discovering and Measuring the Land >> Travellers on the roads of Palestine >>

Travellers on the roads of Palestine >> Palestine explored: the Pioneers >>

Palestine explored: the Pioneers >> Palestine dissected: Guérin and the Survey of Western Palestine >>

Palestine dissected: Guérin and the Survey of Western Palestine >> Further Reading >>

Further Reading >>

Part I: Discovering and Measuring the Land

From the Bronze Age (IIIrd millenium BC) to the modern era, Palestine underwent a series of cycles of expansion, stagnation, decline and regeneration brought to light by Coote and Whitelam (1987, 31). The last episode of "rebirth" was not that of "the desert made to bloom" of the Zionist dream come true with the unilateral proclamation of the creation of the State of Israel on 15th May 1948, but a slow process of urban and rural change and development in Ottoman Palestine in the aftermath of the Crimean War (1855-1856) which culminated on the eve of the First World War (1914-1918).

The XIXth century Rediscovery of Palestine

Bonaparte’s"Expédition d’Egypte" and Jacotin’s Map

When Napoleon Bonaparte, having conquered Egypt in July 1798 (Dauphin, 2009), invaded Palestine on 22nd February 1799, it was but a neglected province of a declining Ottoman Empire, and thus, for Westerners, a terra incognita. His ill-fated pre-Colonial fantasy of Oriental glory reached out to India in which were already involved his arch-enemies, the British, through the East India Company. While the French army was marking time in front of the walls of Acre, on 17th April 1799, Bonaparte issued a proclamation in which he invited ‘all the Jews of Asia and Africa to gather under his flag in order to re-establish the ancient Jerusalem’, which was reported by the main French newspaper during the French Revolution, Le Moniteur Universel, on 3 Prairial, Year VII of the French republican calendar, equivalent to 22nd May 1799. It added that he had already given arms to a great number, and that their battalions threatened Aleppo. Propaganda to enlist the support of one of the suppressed minorities of Europe ? In 1806 he was to abolish in countries which he had conquered laws restricting Jews to ghettos, and in 1807, he made Judaism, along with Roman Catholicism and Lutheran and Calvinist Protestantism, official religions of France. Or, was this proclamation destined to bring over to the French side Haim Farhi, the Jewish advisor to the ruler of Acre, Ahmad al-Jazzar, who was the actual commander of the defence of Acre in the field ? Be as it may, this proclamation was seized upon by the Zionists. In 1940, the official periodical of the Zionist Organisation, The New Judaea, published the claim by the Czech lawyer and historian Franz Kobler (1882-1965) of the discovery of a detailed version of Bonaparte’s proclamation, which went much further than a call to liberate Jerusalem. The Kobler version suggests the invitation to the "Rightful heirs of Palestine" to create a Jewish state, and establish "your political existence as a nation among the nations" (Kobler 1976). The document has since been debunked as a forgery (Schwarzfuchs, 1984).

Napoleon’s reckless adventure in Palestine, which completely collapsed with the ignominious retreat of the French from Acre and their aborted attempt to pull out of Palestine by sea from the Bay of Tanturah on 21st May 1799 (Derogy and Carmel 1992), had, however, the merit of "discovering" the country for the first time and mapping large sections of its territory. The 47 sheets at the scale of 1: 1 000 000 of the Map which bears the name of Jacotin (1815), the officer coordinating the team of geographers and civil engineers whom Bonaparte, the "civilising hero", had recruited from the French scientific élite, cover the Nile Valley from Aswan to the Delta, the Delta and the coast of Sinai, as well as six regions of Palestine : al-‘Arish, Gaza, Jerusalem-Jaffa, Caesarea, Acre-Nazareth-The River Jordan, and Tyre-Sidon. These last six sheets constitute the first modern map of Palestine measured by triangulation. They bear numerous names in French and Arabic of mountains, rivers, roads, towns and villages, ruins and historical sites.

Back to Top

Travellers on the roads of Palestine

The Western ‘civilised’ world having discovered the East, the Orient became a compulsory travel destination for educated men and women of means throughout the XIXth century. Between 1800 and 1878, over 2 000 travellers published at least 5 000 books and articles on Palestine. Most of those for whom travelling to the Holy Land fulfilled a spiritual quest, limited their wanderings to Jerusalem and its immediate surroundings, the Judean Hills and the Acre Plaine. They described the lack of comfort during their peregrinations rather than the ‘piles of ruins under the palm trees’ (Loti, 1895, 4), or the villages punctuating their progress. In reconstructing the landscapes of XIXth century Palestine, the value of this travel literature is minimal, to the extent that C. Ritter (1848), who produced a remarkable geographical study of Palestine and Sinai solely on the basis of travel narratives, remarked : ‘In order to obtain even single nuggets of gold, it has often been necessary to pull to pieces great heaps of rubbish’ (Gage, 1866, II, 60). After Bonaparte’s Egyptian Expedition, the rediscovery of Palestine consisted of two stages: individual exploration (1799-1864), followed by exploration conducted by scientific teams from 1865 to the First World War.

Back to Top

Palestine explored: the Pioneers

The "nuggets of gold" of the period of individual exploration are the fruits of individual research of the German U.J. Seetzen (1855-1859) and the Swiss J.L. Burckardt (1822). They were the foundations of the scientific exploration of Palestine (Ben-Arieh, 1983, 31-43). Between May 1805 and May 1807, Seetzen visited the Hauran, the Lebanon, Western Palestine, Transjordan and Sinai, collecting mineral and vegetal samples, drawing in detail the outlines of creeks and wadis, recording hundreds of Greek inscriptions. Between 1810 and 1817, Burckhardt, whose real goal was to penetrate into the heart of Africa (which he did not reach, for he died of dysentery in Cairo in 1817), explored the Hauran, Jaulan, Galilee, the eastern bank of the River Jordan, and the Wadi Arabah Valley, and located Petra. Neither Seetzen, nor Burckhardt were particularly interested in the Christian Holy Places – Burckhardt did not even visit Jerusalem. Deliberately avoiding the well-known and safe roads, both penetrated into the heretofore unexplored regions of Palestine.

Following in the wake of these pioneers, the theologian, linguist and professor of Biblical Literature at the New York Union Theological Seminary, E. Robinson, deserves the title "Father of Research on the Holy Land". Accompanied by his disciple and friend E. Smith, Robinson left Cairo on horseback on 12th March 1838, aiming for Sinai. On their way, Robinson and Smith discovered the Byzantine dead cities of the Negev desert, exploring more particularly Haluza, ancient Elusa. From Beersheva, they travelled to Hebron and Jerusalem. Then, after criss-crossing Judaea, they visited Nazareth and Tiberias, and finally reached Beirut. In the course of two-and-a-half months in Palestine, they took compass readings of over 1 000 sites and recorded names of villages and of ruins by questioning the local population. A general map of Palestine at the scale of 1: 800 000 in two sheets, and two maps at the scale of 1: 100 000 of Jerusalem and of the supposed site of Mount Sinai, illustrate their Biblical Researches (Robinson, 1841). These maps were drawn by the German cartographer H. Kiepert on the basis of thousands of triangulation points and of details of roads, villages and ancient sites provided by Robinson and Smith. In the course of a second trip in 1856, they extended their research to encompass Galilee, Samaria, Mount Lebanon and Damascus (Robinson, 1856). As theologians and Biblical scholars, Robinson and Smith applied themselves to the task of elaborating a new discipline, "sacred historical geography".

Back to Top

Palestine dissected: Guérin and the Survey of Western Palestine (1872-1877)

-

The real foundations of the geographical study of Palestine were established by a solitary French explorer, V. Guérin, and a British team – the Royal Engineers of the Survey of Western Palestine – in the second third of the XIXth century. Guérin visited Palestine for the first time in 1852 at the time of Robinson’s second visit. His last visit in 1875 coincided with the intensive surveys of the Palestine Exploration Fund. He came five times to Palestine, followed the main roads in 1852, but covered the entire country in 1854. His trips in 1863, 1870 and 1875 were undertaken at the request of the Turkish Ministry of Public Works. Guérin’s seven volumes of notes (1868-1874, 188) compete in extent with the three volumes of the Memoirs of the Survey of Western Palestine (Conder and Kitchener, 1881-1883) – an astonishing feat for a single individual. In fact, Guérin’s work and the Memoirs of the Survey of Western Palestine complement each other.

Funded by British philanthropists, the first scientific cartographic survey of Jerusalem, which for the first time made use of the budding "science" of photography, was conducted in 1864-1865 by a team of Royal Engineers headed by C. Wilson. This survey aimed at exploring and recording in detail the water supply system of the Holy City, which periodically suffered from lack of water (Howe 1997, 29-35). Published by the British War Office (Wilson, 1866), it demonstrated that scientific team work could achieve much more than individual efforts. It also opened the way for the founding in London on 12th May 1865 of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) under the patronage of Queen Victoria. In the course of the inaugual meeting of the PEF on 22nd June 1865, the Archbishop of York, William Thomson, stated: "We are about to apply the rules of Science… to an investigation into the facts concerning the Holy Land" (PEF Report of Proceedings 1865, 3). The establishment of the PEF and its aim to conduct scientific work should be viewed against the background of controversies which Darwin’s evolutionist theories had roused in the Victorian Anglican Church (Lipman, 1988, 45-46). The scientific work was to consist of "investigating the archaeology, geography, geology and natural history of the Holy Land".

Following four preliminary expeditions in Northern Palestine in 1865-1866, in Jerusalem in 1867-1870, Sinai , and Negev, the Palestine Exploration Fund finally turned to its main goal: the general survey and mapping of Western Palestine. This tas kwas entrusted to Stewart who, struck by malaria, was compelled to return to the United Kingdom and was replaced at first by C. Tyrwhitt-Drake, and ultimately by C. Conder. From 1875, directing the team was shared by Conder with the future Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, then only a young officer in the Royal Engineers corps. The survey of Palestine, from Tyre and Banyas in the north to Gaza and Beersheva in the south, were completed in September 1877 (Gibson, 1997).

In 1850-1851, the Frenchman F. de Saulcy with a team comprising a photographer, a mapper, an architect and a botanist, produced an archaeological map of the Dead Sea (Caubet, 1982, 184-185). This map, however, was of a single region of Palestinian territory. Conder could therefore rightly flatter himself to have been with his team "the first to gather that complete account of the country, of its ancient remains, and of its present inhabitants" (Conder, 1891, 1). The 26 cartographic sheets at the scale of one inch to a mile, which cover the whole of Palestine from Dan to Beersheva, were produced on the basis of precise theodolite readings and by triangulation, according to the method followed by the Ordnance Survey of Great-Britain (Conder, 1891, 59-60; Hodson, 1997).

-

These 26 sheets illustrate the three volumes of Memoirs. To each sheet corresponds a chapter of text which describes systematically and in detail the landscape, topography, agriculture, hydrography, the roads, towns and villages listed alphabetically and according to Ottoman administrative districts, the population, religions, historical sites and archaeological ruins. References as full as possible are also provided to the Jewish, Samaritan, Greek, Latin, Arabic and Crusader historical sources.

From its onset, the Survey of Western Palestine represented half of a double project, the other half - the survey of Transjordan following identical methods - was undertaken from 1872 in collaboration with the PEF by its trans-Atlantic sister, the American Palestine Exploration Society, which had been founded in 1870 in New York. In the early 1870s, in contrast to "densely settled and relatively civilised Western Palestine" (Cobbing, 2005, 11), the land east of the River Jordan was largely untracked and difficult to explore: "At this time, the Turkish administration was struggling to maintain a semblance of control over the fiercely independent and often warring Bedouin tribes that loosely populated the territory. Supplies and settlements were few and far between, and the terrain was, for the most part, rugged and apparently desolate" (Cobbing, 2005, 11). Lack of experience and problems of funding drove the American Society to abandon in August 1877 its "reconnaissance" work. The discrepancies between the American Map (described as "inexact" by Besant, the Secretary of the English PEF) and the SWP maps led the PEF to conduct its own survey in Ammon and Moab in 1881, directed by C. Conder, but the "Eastern Survey" was also abandoned owing to prolonged waiting for a firman from the Ottoman administration. The maps of Transjordan and of the Jaulân were eventually drawn by the German railway engineer G. Schumacher (1886; 1888; 1889) for the Deutsche Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas founded in 1877, the Palestine Exploration Fund and the Turkish Railways. His maps of the same format and at the same scale as those of the Survey of Western Palestine are their complement. His archaeological explorations cross-check the discoveries of L. Oliphant (1880; 1885 ; 1886; 1887), an erudite, versatile and excentric Victorian Scot, author and journalist, part diplomat and/or secret agent in Her Majesty’s Service, former Member of Parliament and religious mystic, intent on settling the Land of Gilead with survivors of the anti-Jewish pogroms in Rumania and Russia, and the first non-Jewish Zionist to buy a house in Haifa and thus put into practice his belief (Amit 2007, 205-206).

In 1883, the geographer E. Hull and Kitchener led an expedition in the Wadi ‘Arabah Valley with the aim of mapping the region between Mount Sinai and the Wadi ‘Arabah, edged on the west by the plateau of Tih and by the mounts of Edom (Hull, 1885; 1886; 1910).

In the Negev, the Survey of Western Palestine had stopped at an imaginary line between Gaza and Beersheva and at the Egyptian border from Rafah to the Gulf of ‘Aqaba. The mapping of the Negev proper was undertaken only in 1913 by S.F. Newcombe and F.C.S. Greig. Attached to the team of topographers, the archaeologists C.L. Woolley and T.E. Lawrence - soon to become Lawrence of Arabia -, examined the Byzantine caravan cities of which they drew the first plans (Woolley and Lawrence, 1914-1915). The map of the Negev was classified until the victory of the Allies over the Ottoman Empire. If glaring proof were needed of the intertwining of surveying for mapping, recording the lay of the Land, its physical features and the names of its localities, with empire-building, it is provided by the classified map of the Negev prior to General Allenby’s progress from Egypt to Gaza, and onto Jerusalem which he entered on 9th December 1917. The military dimension of the Survey of Western Palestine was flagrant: the War Office was the first recipient of the SWP maps. In the same vein, collecting Celtic place-names and translating them into English by a cartographer and an orthographer working in 1833 in a small village of County Donegal on the six-inch-to-the-mile map of Ireland for the Ordnance Survey (whose logo included the War Department’s broad arrow heraldic mark) in Brian Friel’s 1980 play Translations, signified the consolidation of the Colonial hold over land and people, and its counterpart, the long-term destruction of Irish culture and language.

Back to Top

Further Reading

| Amit, Th. 2007. | "Laurence Oliphant : Financial Sources for his Activities in Palestine in the 1880s", Palestine Exploration Quarterly Vol. 139, No. 3 (November 2007), 205-212. |

| Ben-Arieh, Y. 1983. | The Rediscovery of the Holy Land in the Nineteenth Century, The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University and Israel Exploration Society, Jerusalem. |

| Burckhardt, J.L. 1822. | Travels in Syria and the Holy Land, London. |

| Caubet, A. 1982. | "La Palestine de Saulcy", in Félix de Saulcy et la Terre Sainte, Musée d’Art et d’Essai. Palais de Tokyo, avril-septembre 1982. Notes et Documents des Musées de France 5. Ministère de la Culture. Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 184-187. |

| Cobbing, F. J. 2005. | "The American Palestine Exploration Society and the Survey of Eastern Palestine", Palestine Exploration Quarterly Vol. 137, No. 1, April 2005, 9-21. |

| Conder, C.R. 1891. | Palestine, George Philip and Son, London- Liverpool, 1892 (2nd ed.). |

| Conder, C.R. and Kitchener, H.H. 1881-1883. | Memoirs of the Survey of Western Palestine. I. Galilee (1881); II. Samaria (1882); III. Judaea (1883), London. |

| Coote, R.B. and Whitelam, K.W. 1987. | The Emergence of Early Israel in Historical Perspective, The Almond Press, Sheffield. |

| Dauphin, C. 2009. | "Bonaparte in Egypt: The Sword and the Intellect", Minerva, Vol. 20, No. 2, March/April 2009, 16-21. |

| Derogy, J. and Carmel, H. 1992. | Bonaparte en Terre Sainte, Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris. |

| Friel, B. 1980. | Translations, Faber and Faber, London. |

| Gage, W.L. 1866 ed. | The Comparative Geography of Palestine and the Sinaitic Peninsula by C. Ritter, Edinburgh. |

| Gibson, S. 1997. | "Officers and Gentlemen", Eretz No. 52 (May-June 1997), 19-25. |

| Guérin, V. 1867-1874. | Description de la Palestine. Judée. I-III (1868), Samarie. I- II (1874),Galilée. I-II (1880), Paris. |

| Hodson, Y. 1997. | "Mapping It Out", Eretz No. 52 (May-June 1997), 43-50. |

| Howe, K.S. 1997. | "Revealing the Holy Land. Nineteenth Century Photographs of Palestine", in Revealing the Holy Land. The Photographic Exploration of Palestine, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1997, 16-46. |

| Hull, E. 1885. | Mount Seir, Sinai and Western Palestine, London. |

| Hull, E. 1886. | The Geology of Palestine and Arabia Petraea, London. |

| Hull, E. 1910. | Reminiscences of a Strenuous Life, London. |

| Jacotin, M. 1815. | Carte Topographique de l'Egypte et de plusieurs parties des pays limitrophes levée pendant l'expédition de l'Armée Française, Paris. |

| Kobler, F. 1976. | Napoleon and the Jews, Schocken Press, New York. |

| Lipman, V.D. 1988. | "The Origins of the Palestine Exploration Fund", Palestine Exploration Quarterly (1988), 48-54. |

| Loti, P. 1895. | Jérusalem, Calmann Lévy, Paris. |

| Oliphant, L.1880. | The Land of Gilead, London. |

| Oliphant, L. 1885. | "Explorations North-East of Lake Tiberias and in Jaulan", Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Studies (1886), 82-97. |

| Oliphant, L. 1886. | "New Discoveries", Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Studies (1885), 73-81. |

| Oliphant, L. 1887. | Haifa or Life in Modern Palestine, William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh-London. |

| Robinson, E. 1841. | Biblical Researches in Palestine, London. |

| Robinson, E. 1856. | Later Biblical Researches in Palestine, London. |

| Schumacher, G. 1886. | Across the Jordan, Richard Bentley and Son, London. |

| Schumacher, G. 1888. | The Jaulân, Richard Bentley and Son, London. |

| Schumacher, G. 1889. | Northern Ajlun, Richard Bentley and Son, London. |

| Schwarzfuchs, S. 1984. | Napoleon, the Jews and the Sanhedrin, Oxford University Press USA, 1964. |

| Seetzen, U.J. 1854-1859. | Reisen durch Syrien, Palastina, Phonicien, Berlin. |

| Wilson, C.W. 1866. | The Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, Vols I-III, Southampton. |

| Woolley, C.L. and Lawrence, T.E. | 1914-1915. The Wilderness of Zin. PEF Annual, Third Volume; repr. 1903, Palestine Exploration Fund, London. |

1

1